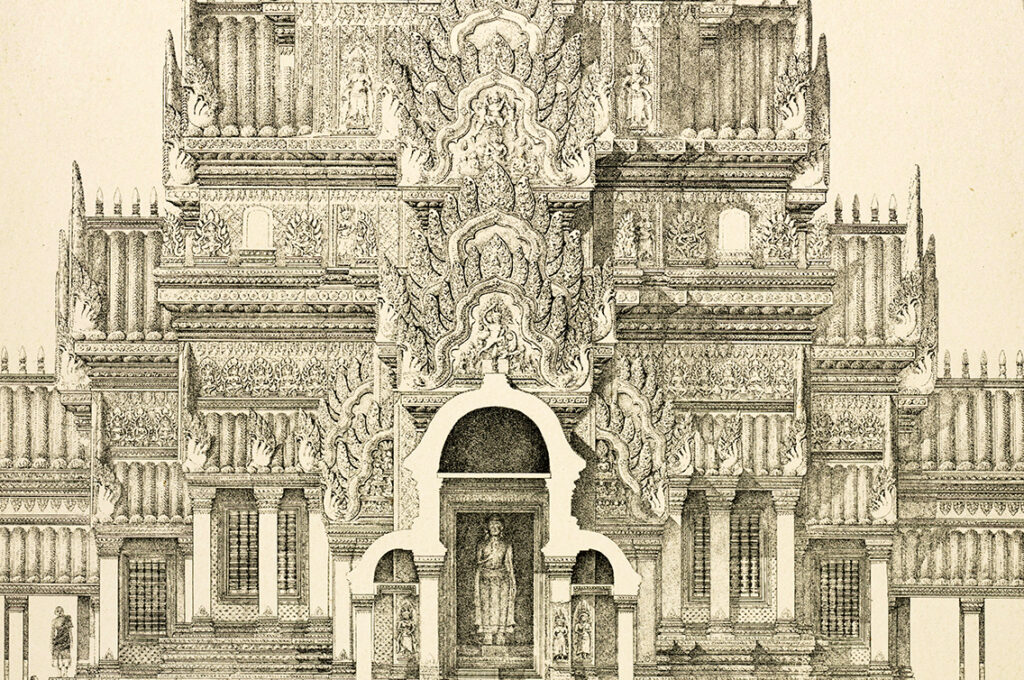

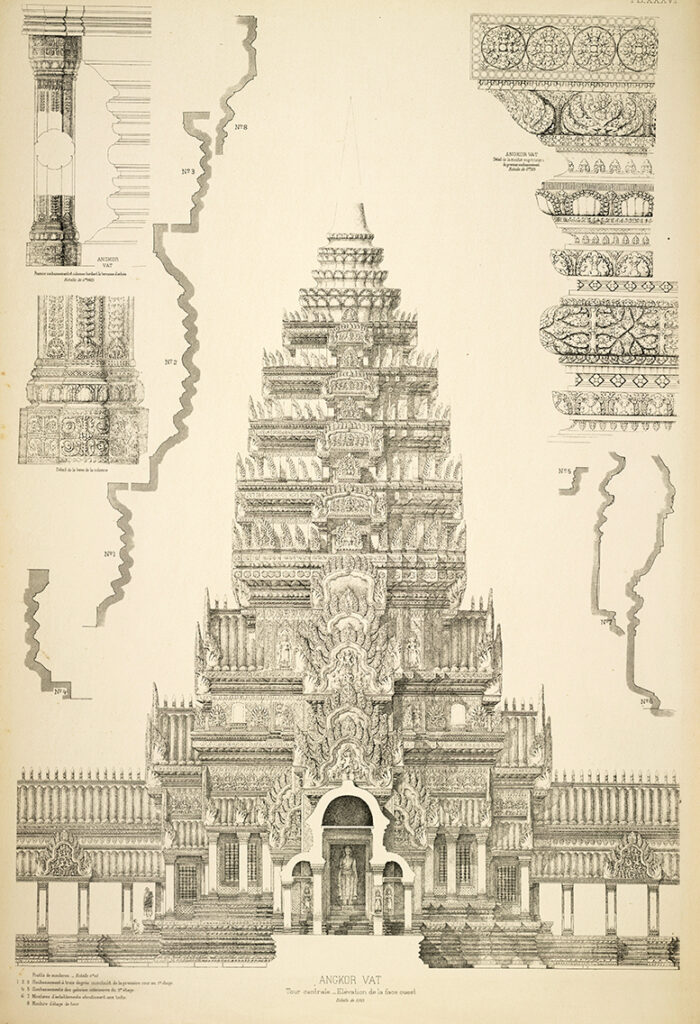

Angkor Wat is a prodigy of craft. It is handiwork carried to perfection, the reign of resolve, the domain of leafy flourishes, petals, lapidary embroidery. Line is its tyrannical queen. The layout is glacial. Stone, rigid stone, is a goddess. The zeal for decoration, the will to dazzle, bursts forth from every block.

George Groslier (1913)

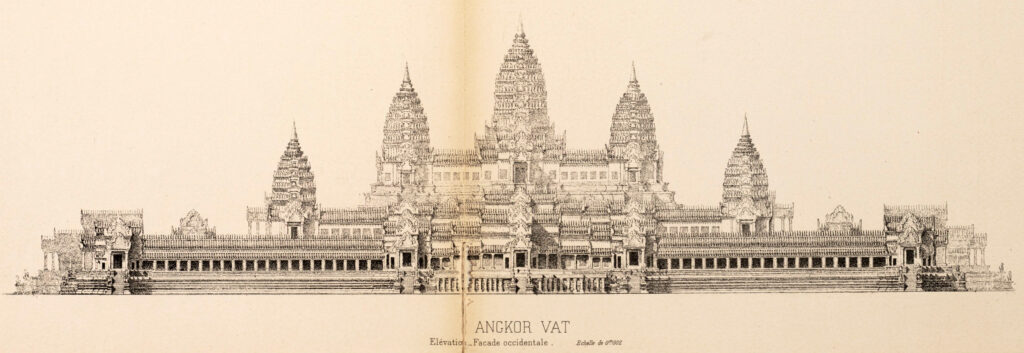

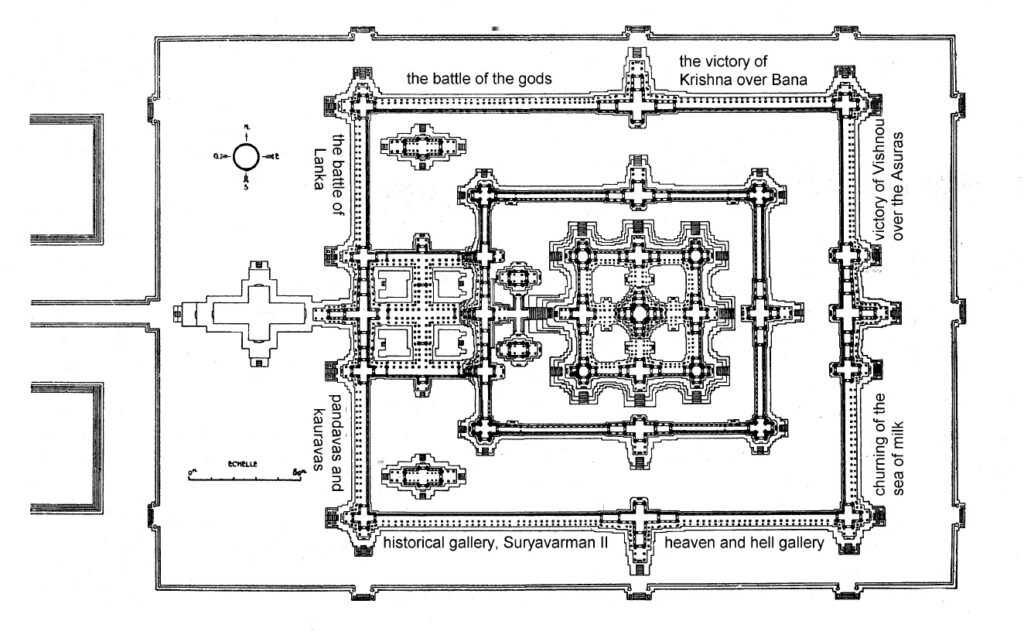

Showcasing the very zenith of Khmer temple building traditions, Angkor Wat, commissioned by Suryavarman II (r. 1112-1152 CE) is the largest religious sanctuary in the whole world. This is an unbelievably outrageous manmade megastructure; literally impossible to express in words and capture in cameras. This can only be experienced. Frank Vincent, author of “The land of the White Elephant” and amongst the first few to photograph Angkor Wat notes, “The general appearance of the wonder of the temple is beautiful and romantic as well as impressive and grand … it must be seen to be understood and appreciated.” The grandness of Angor Wat is difficult to apprehend even when you are physically there. I whole-heartedly agree with Dawn Rooney who feels, “The plan of Angkor Wat is difficult to grasp when walking through the monument because of its enormity. Its complexity and beauty both attract and distract one’s attention. From a distance, Angkor Wat appears to be a colossal mass of stone on one level with a long causeway leading to the centre, but close up it is a series of elevated towers, covered galleries, chambers, porches and courtyards on different levels linked by stairways.”

So, is grandness the only thing that makes Angkor Wat iconic? Is the largest religious monument all about expansiveness? But then, what makes it the most photographed monument in the whole world? Well! It is much more than merely the enormous scale. It is about symmetry and balance; about artistic and aesthetic excellence; about elegant proportions and immaculate detailing; about layers of mythology and unbound imagination. All these elements are blended accurately to create a masterpiece that leaves an imperishable impact. Somerset Maugham professes, “I have never seen anything in the world more wonderful than the temples of Angkor, but I do not know how on earth I am going to set down in black and white such an account of them as will give even the most sensitive reader more than a confused and shadowy impression of their grandeur. Of course to the artist in words, who takes pleasure in the sound of them and their look on the page, it would be an opportunity in a thousand. What a chance for prose pompous and sensual, varied, solemn and harmonious; and what a delight to such a one it would be to reproduce in his long phrases the long lines of the buildings, in the balance of his paragraphs to express their symmetry, and in the opulence of his vocabulary their rich decoration! It would be enchanting to find the apt word and by putting it in its right place give the same rhythm to the sentence as he had seen in the massed grey stones; and it would be a triumph to hit upon the unusual, the revealing epithet that translated into another beauty the colour, the form and the strangeness of what he alone had had the gift to see.”

Despite being the largest Hindu temple, Angkor Wat dedicated to Lord Vishnu has many contradictions tucked within its grandeur. Unlike the other Hindu temples, Angkor Wat suspiciously faces west, and not east. Scholars attributed this anomaly to the structure, first being a temple and later turned into a funerary cenotaph. Commenting on the matter Glaize points out, “This orientation to the west, in contrast to the other Angkor monuments which face the rising sun, initially gave cause for much confusion – some seeing a simple topographic necessity where others saw ritual organisation.” He adds, “Due to research by Mssrs Finot, Coedes, Przyluski and Dr Bosch, the Head of the Service Archéologique des Indes Néerlandaises, it seems proven that Angkor Wat is in fact a funerary temple, and the only one built during the life of the founding king – Suryavarman II – for his consecration, and probably also as a depository for his ashes.” This theory is also supported by the anti-clockwise arrangement of bas-reliefs in the temple galleries. The temple was later transformed into a Buddhist monastery under Jayavarman VII (r. 1181-1219/20 CE).

Spread over 200 hectares, the ground plan is unprecedented with three elaborate enclosing galleries studded with bas-reliefs of premium workmanship. As we move towards the center, the sub-structures rise up elegantly in elevation to accentuate the visual aesthetics. The central tower over the main sanctum rises above the neighboring four towers on the third enclosing wall to represent the mythical mount Meru. Writing about the architecture Glaize remarks, “If Angkor Wat is the largest and the best preserved of the monuments, it is also the most impressive in the character of its grand architectural composition, being comparable to the finest of architectural achievements anywhere. By means of its perfectly ordered and balanced plan, by the harmony of its proportions and the purity of its lines – of a solemnity that one rarely encounters in the Khmer themselves – and by the very particular care taken in its construction, it merits being placed at the apogee of an art that can occasionally surprise in its complexity and poor craftsmanship. This temple is the one that comes closest to our Latin ideas of unity and classic order, born of a symmetry responding to the emphatic axes. Angkor Wat is a work of power and reason.”

Angkor is an overwhelmingly impactful experience; if historian Milton Osborne thinks “The temples at Angkor were what brought travellers to Cambodia,” Norman Lewis considered, “Angkor Wat in a league of its own: the most spectacular man-made remains in the world.” About the haunting charm of these ruins, Glaize mentions, “An American visitor, in her enthusiasm for Angkor, made the request that her ashes be scattered on the causeway of Angkor Wat – a satisfaction granted to her at the beginning of 1936. Such a gesture symbolises the extraordinary power which these ancient ruins have on peoples’ imagination.” Similar feelings are echoed by Groslier who notes, “For two years I had seen it only in my mind, recalling my first, nearly three-month stay. In the interval I had lived the active life of youths who seek their way, eyes fixed on their goal even in the midst of Paris and all its temptations. It was Angkor that I had fought for, Angkor that had held my gaze through the window of my atelier, and its wonders were always on my lips.”

Practicalities | Angkor Wat is larger than life; larger than Cambodia; and certainly larger than any manmade structure that you are likely to see. To visit Angkor, all tourists require an Angkor Pass – $37 for 1-Day, $62 for 3-Days, and $72 for 7-Days. Go for a week long pass if you have time as the whole area has a galaxy of temples to explore. Angkor remains busy throughout the day; start early to avoid rush. Take time to soak in; a guide is highly recommended for understanding the bas-reliefs. I am in unison with Glaize who feels, “Whatever one may think, Angkor Wat merits a number of visits – and at least two – one for the monument and another dedicated to the bas-reliefs. If these can be seen in the morning, when the light is clear, then the rest should best be seen at the end of the day as the towers become increasingly golden with the sun sinking to the horizon.” In addition to the above, do go for the aerial views made possible through a tethered balloon or helicopter sorties (if you can afford).